Common problems adopting Shape Up

Here are some common problems that happen when people try to do Shape Up “by the book.” Most of them have to do with the differences between Basecamp/37signals and real-world teams. There are two main differences between Basecamp and the real world:

- Basecamp has no external investors, no board, no outside pressures. The urgency to ship is driven internally by the founders and the team culture.

- At Basecamp, there is almost no gap between technical and non-technical people. Every person in the product team (as of when I wrote the book) can code or was hands-on involved in coding in the past. This means there is no surprising “moment of truth” when a designer brings an idea to an engineer.

Despite these differences, hundreds of teams have been able to adapt Shape Up to work for them. But if you're trying to do it by the book, and don’t know about these differences, it can lead to some misunderstandings.

Problem: "Six weeks is too long"

If six weeks feels too long, you’re not alone. There can be good reasons for this. When you have targets you need to hit because of investor or board pressures, you want to move as fast as possible. There can be meaningful things you can do in 2-3 weeks that would move the needle on activation or churn. In that case, think of 6 weeks as the maximum time commitment for a single cycle, not a fixed number. You can give yourself the flexibility to define a time box shorter than that. The key is that you determine that fixed amount of time up front and shape what goes *into* that time so the time is spent successfully.

Suppose you want to make a change to your onboarding flow and you’re willing to spend two weeks on it. You don’t want the change to spiral out of control when you bump into complexities. And it might not have been easy to get alignment on spending engineering time on this thing. So it makes sense to dedicate a couple days to carefully shaping the project before kicking it off. Then you can be confident the time will be spent well and you’ll ship within the appetite.

Problem: "Cycles run into cool-down"

When the build team isn’t finishing projects in the time given, this points to a problem in the shaping before kick-off, not within the cycle itself.

Ask yourself: Was engineering involved in the shaping? Or was it shaped by a PM and designer without an engineer?

When the shaping is done by a PM alone, it’s usually too high-level and fuzzy. The PM puts a lot of work into describing the outcome, the business case, what customers care about, etc. But that doesn’t tell the engineers what to go build. Think of building a house. You can have all kinds of good reasons for why you want the house, how many rooms, the total you want to spend, etc. But when the contractors arrive at the building site, the clock starts ticking. They need a blueprint! Without a clear concept of the solution up front, there will be a million questions, long discussions, and expansion in scope.

When shaping is done by designers who aren't engineers, the work they produce has too much of the wrong detail in it. High-fidelity drawings create an illusion of clarity because you can point at them and say “this is what we should build.” But the drawings don’t take the technical realities into account. So when the drawings are shown to engineers, there’s pushback, unanswered questions, and unwelcome trips back to the drawing board. In our imaginary house project, it’s like the contractors arrive at the building site, and you hand them a full-color rendering of the kitchen interior. They see the color of the tiles and design of the cabinets. But they don’t have answers to the basic questions about the foundation, walls, and plumbing.

The way out of this is to bring a senior technical person into the shaping from the beginning and work together in live sessions. You want to surface the unknowns and hard technical questions as early as possible, before a designer puts their heart and soul into pixel-perfect mockups and before you make commitments about what will ship. We teach how to run these live shaping sessions in Shaping in Real Life.

You might wonder how it’s possible for PMs, designers, and engineers to actually cooperate together. Breadboarding is very useful for this. Here’s an example of what it looks like to work through an idea using a breadboard in a live shaping session:

Problem: "We have to cut too much scope"

Some teams try to solve the problem of finishing on time by cutting lots of scope. But cutting so much scope means the value isn’t there. It doesn’t do what it’s supposed to. Now you have a bunch of stuff you didn’t do that still has to be there somehow. There’s no “win” at the end. People question why they’re using this new way of working when there’s no payoff. It’s a quick road back to scrum.

This is caused by misunderstanding the idea of “fixed time, variable scope.” Typically a non-technical founder/CEO thought they could set an appetite, describe the outcome, and tell the team to just “vary the scope” to get it done. This doesn’t work. As my friend Bob likes to say, “you can’t put ten pounds of dirt in a five-pound bag.”

Shaping is figuring out what we can actually build that fits the constraints and does what we want. It’s not waving a magic wand — it’s solving the puzzle! This gets back to bringing product and engineering together. To solve the puzzle we need product’s knowledge of the customer and engineering’s knowledge of what is technically possible.

If you’re not hitting cost and complexity problems while shaping, you’re not getting concrete enough. Whiteboarding specific ideas is how we surface problems. Our task in a shaping session is to first surface problems and then resolve them. We’re done when we reach a point where we can look each other in the eye and say “yes, this is going to work.”

That clarity emboldens us to set a fixed time. And that same clarity is, surprisingly, what enables the team to vary the scope. Have a look again at the Calendar concept in Chapter 2 of the book. That is a very specific, achievable idea. At the same time, there are a million implementation decisions to make. The team is able to make judgement calls along the way because they know what they are aiming for.

Problem: "We can’t make time to shape"

Once product people realize they should involve engineers in shaping, a challenging appears: How do we make time for that? It’s already so hard to get time from engineers. And we have so many ideas — we can’t hold a shaping workshop for every idea.

The book gave the impression that at Basecamp we were shaping many different ideas and only at the last minute, before a cycle started, we decided which one to build. I didn’t realize until after I left Basecamp that there was an invisible process going on behind the scenes that I didn’t have a name for. All the time, I was having side conversations with leadership about what was important to them, what they considered urgent, and which problems popping up from different corners of the company felt “real” to them.

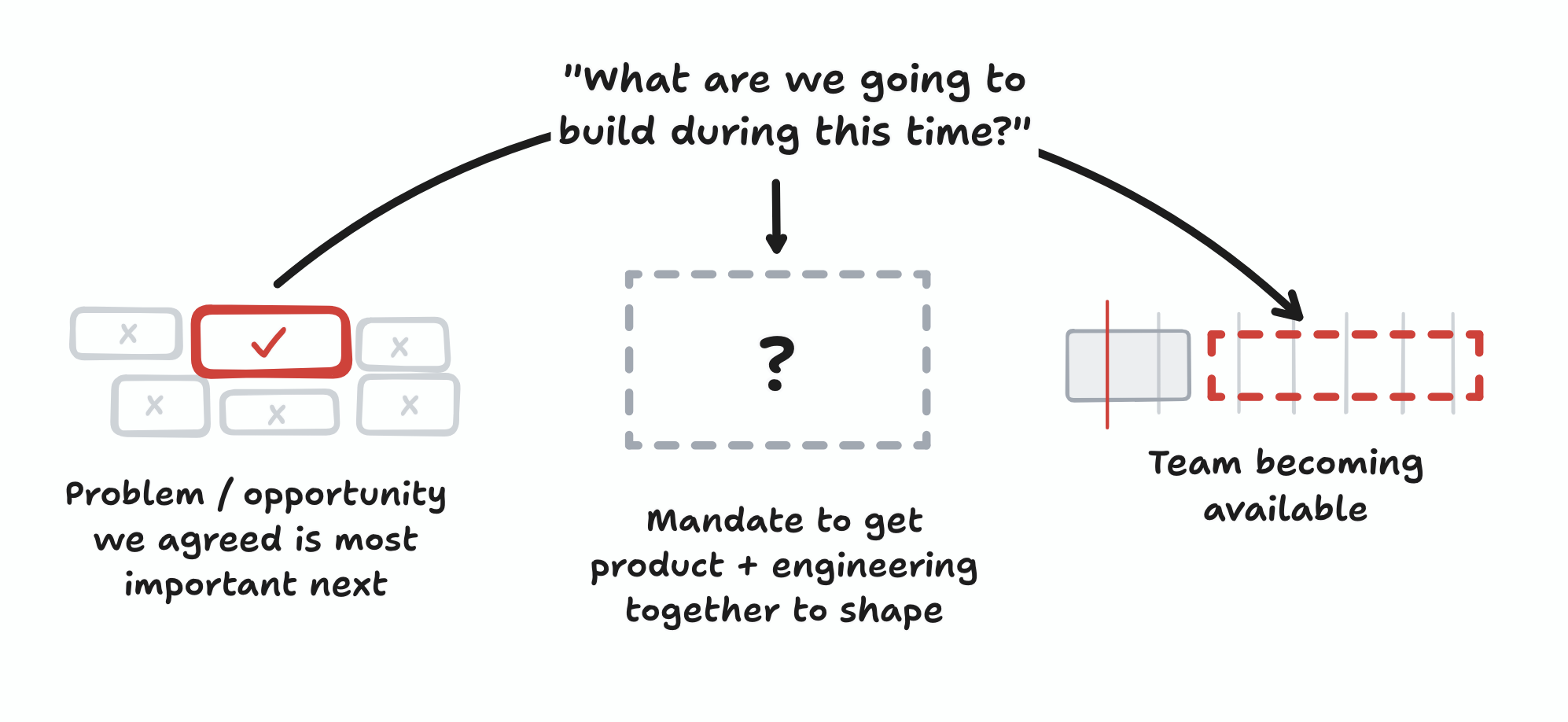

In Shaping in Real Life, we call this work “framing.” It’s the work of narrowing down the problem, weighing it against other problems and opportunities, and coming to agreement on what deserves the time to shape and build. Think of framing as working on the problem, and shaping as working on the solution.

When we’ve done the work to hone in on a problem and we're aligned with leadership that this thing, out of everything, is the thing we want to do next, then we have the mandate we need to make time for shaping.

Get past these problems

I hope this gives you some inspiration to get through these problems and avoid backsliding to scrum or whatever the team did before Shape Up.

If you want more detail on how to make Shape Up work in a team that isn't structured like Basecamp, check out Shaping in Real Life.

If you need to inspire the team to "unlearn" certain dogmas, you can reach out to me about speaking to your team.

If your org already went through an attempt at Shape Up and it didn't work out, you might feel hesitant to try again. Usually there's only so much tolerance for experimenting with ways of working. If you need to get the team moving faster again, but you don't have much room for mistakes or trial-and-error, check out Get Unstuck.